Featured Article:

Leandro Bisiach I

His Life & Art

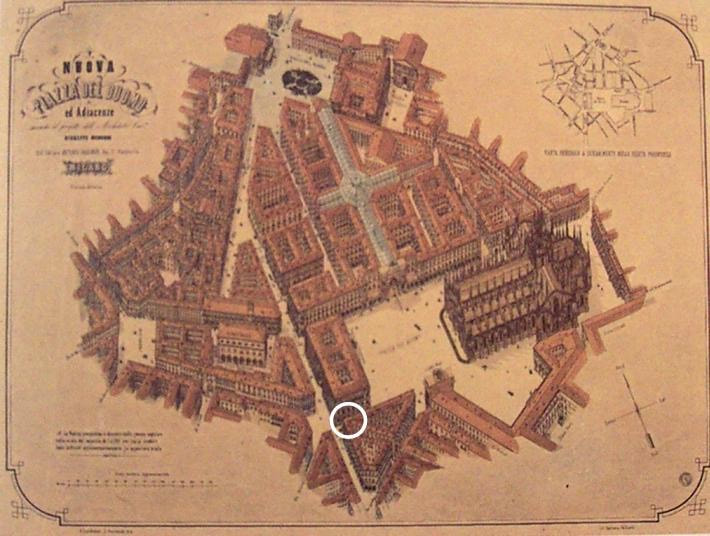

The Piazza del Duomo in Milan, 1909. During this time, Bisiach's workshop occupied the building pictured right (the corner just out of frame).

Giuseppe Leandro Bisiach (b.1864, d.1945) is a pivotal figure in the history of modern violinmaking. Known simply as Leandro Bisiach (I), he is regarded in an analogous fashion to the famous violin maker, dealer and connoisseur, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (b.1798, d.1875). Both employed many of the most talented contemporaneous makers and founded the most important and successful violin businesses of their respective regions and eras. At an early age, Bisiach had quickly moved from apprentice to master luthier and by the turn of the last century, had established the most lauded and commercially rewarding violin business in all of Italy and among the very best in Europe. He was largely responsible for reviving and promoting the old Cremonese tradition and infused it with new creative energy which carries on to this day.

Although Bisiach's commercial success is well documented, other aspects of his working life are largely overshadowed by his business achievements. It may be useful to consider his life in interconnected parts - musician, luthier, connoisseur, entrepreneur and father. Each of these aspects was key integral to his success. What emerges from this view, is a picture of a man wholly dedicated to the art of the violin.

Although Bisiach's commercial success is well documented, other aspects of his working life are largely overshadowed by his business achievements. It may be useful to consider his life in interconnected parts - musician, luthier, connoisseur, entrepreneur and father. Each of these aspects was key integral to his success. What emerges from this view, is a picture of a man wholly dedicated to the art of the violin.

TIMELINE

1864: Jun. 16 - Leandro Bisiach I is born in Casale Monferrato

1886: Moves to Milan / Begins studying with the Antoniatzzi Family - Last heirs to what remains of the great Cremonese tradition

1890: Dec. 16 - Birth of Andrea Bisiach / Establishes his first shop near the Piazza del Duomo (later relocates to better premises at the corner of the Piazza)

1892: Mar. 9 - Birth of Carlo Bisiach

1900: Establishment of Bisiach Violin Shop / Nov. 28 - Birth of Giacomo Bisiach

1901: Gaetano Sgarabotto joins the Bisiach workshop in Milan

1904: Birth of Leandro Bisiach II

1905: Sgarabotto leaves the Bisiach workshop to work independently

1907: Leandro Bisiach visits Genoa and views Paganini's famed 1743 Guarnerius, 'Il Cannone'.

1912: Death of Riccardo Antonianzzi

1914: Italy enters into the First World War

1916: The Bisiach family leaves Milan and relocates family to Sienna / Becomes curator to the important collection of Count Guido Chigi-Saracini

1917: Bisiach meets Igino Sderci and begins training him.

1922: The Bisiach family returns to Milan and reopens the shop / Carlo marries pianist, Daria Guidi and stays on with Sderci in Sienna

1926: Carlo Bisiach and Sderci relocate their workshop to Florence where they remain collaborators of Leandro's Bisiach's Milan shop.

1928-1937: Gaetano Sgarabotto directs the violin making school in Parma

1940: Italy enters into the Second World War / First bombings of Milan

1942-45: Major Allied bombings of Milan. The worst of the bombings were August 12-13, 1943. The Bisiachs lost much many treasures in this tragedy.

1945: Dec. 1 - Death of Leandro Bisiach I / His sons carry on the business / They and his former employees carry on the great Milanese tradition.

1967: Death of Andrea

1968: Death of Carlo

1973: The Bisiach Firm closes after 83 years in business. Leandro II continues making violins from home for the remainder of his life.

1982: Death of Leandro II

1983: Death of Igino Sderci

1995: May 8: Death of Giacomo

Present: The decendents of Dario Vettori I and Renato Scrollevezza, among others, continue the violinmaking tradition ignited by the Bisiachs.

Giacomo Bisiach II maintains the Bisiach Villa (Villa Puccini) in Venegono which houses many letters, painting, casts, and instruments.

1864: Jun. 16 - Leandro Bisiach I is born in Casale Monferrato

1886: Moves to Milan / Begins studying with the Antoniatzzi Family - Last heirs to what remains of the great Cremonese tradition

1890: Dec. 16 - Birth of Andrea Bisiach / Establishes his first shop near the Piazza del Duomo (later relocates to better premises at the corner of the Piazza)

1892: Mar. 9 - Birth of Carlo Bisiach

1900: Establishment of Bisiach Violin Shop / Nov. 28 - Birth of Giacomo Bisiach

1901: Gaetano Sgarabotto joins the Bisiach workshop in Milan

1904: Birth of Leandro Bisiach II

1905: Sgarabotto leaves the Bisiach workshop to work independently

1907: Leandro Bisiach visits Genoa and views Paganini's famed 1743 Guarnerius, 'Il Cannone'.

1912: Death of Riccardo Antonianzzi

1914: Italy enters into the First World War

1916: The Bisiach family leaves Milan and relocates family to Sienna / Becomes curator to the important collection of Count Guido Chigi-Saracini

1917: Bisiach meets Igino Sderci and begins training him.

1922: The Bisiach family returns to Milan and reopens the shop / Carlo marries pianist, Daria Guidi and stays on with Sderci in Sienna

1926: Carlo Bisiach and Sderci relocate their workshop to Florence where they remain collaborators of Leandro's Bisiach's Milan shop.

1928-1937: Gaetano Sgarabotto directs the violin making school in Parma

1940: Italy enters into the Second World War / First bombings of Milan

1942-45: Major Allied bombings of Milan. The worst of the bombings were August 12-13, 1943. The Bisiachs lost much many treasures in this tragedy.

1945: Dec. 1 - Death of Leandro Bisiach I / His sons carry on the business / They and his former employees carry on the great Milanese tradition.

1967: Death of Andrea

1968: Death of Carlo

1973: The Bisiach Firm closes after 83 years in business. Leandro II continues making violins from home for the remainder of his life.

1982: Death of Leandro II

1983: Death of Igino Sderci

1995: May 8: Death of Giacomo

Present: The decendents of Dario Vettori I and Renato Scrollevezza, among others, continue the violinmaking tradition ignited by the Bisiachs.

Giacomo Bisiach II maintains the Bisiach Villa (Villa Puccini) in Venegono which houses many letters, painting, casts, and instruments.

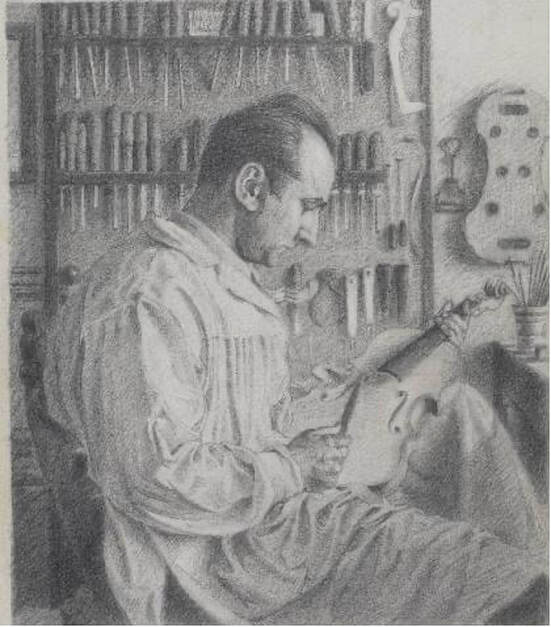

Leandro Bisiach I in his Workshop

The Bisiach family originated from the Dalmatian region of the Adriatic coast (present day Croatia). This region was formerly in the Repubic of Venice. It is unknown why the Bisiach family migrated. Born in Casale Monferrato in the Piedmont region, Leandro Bisiach began playing the violin from an early age. It is certain that he was an exceptionally gifted musician. After moving to Milan he performed regularly on a professional basis with the finest quartets and orchestras in the city. He would have been well positioned to make the acquaintance of a large number of string players. He considered some of most celebrated musicians and composers of all time his close personal friends. Violin virtuoso, Pablo de Sarasate and Brahms-collaborator, Joseph Joachim as well as the great cellist, Alfredo Piatti were among these friends who were early patrons of his shop. In fact, Bisiach made copies of one of Sarasate's Stradivarius violins as well as one of Piatti's cello. It is sometimes difficult for musicians and luthiers to communicate the nuances of their respective crafts to each other. Having a foot in both camps was probably invaluable to Bisiach's ability to develop and maintain his relationships with his clients. That so many of his clients were also his friends certainly helped cement those professional bonds and it is admirable that this stemmed from a genuine passion for his life's art. No doubt his ability as a luthier and restorer was largely informed by the sharp-ears he would have developed as a musician. Bisiach's sons who were to join him in his business also played string instruments at a high level of ability. Music and art were facts of life for the Bisiach family and their musical ability would have been indispensable to their craft.

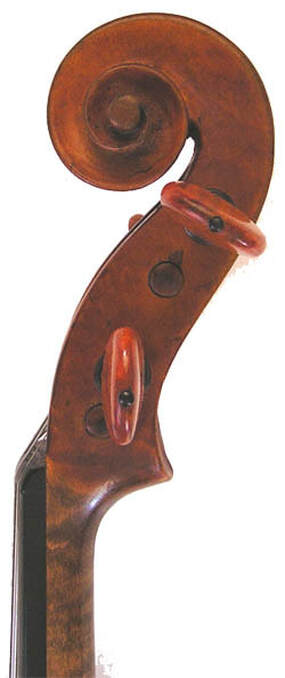

In addition to playing the violin from an early age, it is probable that Bisiach made one or more attempts at violinmaking, potentially as a self-taught endeavor, before moving to Milan and training with Riccardo Antoniazzi (b.1853, d.1912) from 1886. In just three short years, Bisiach had opened his own establishment, collaborating with and eventually employing his former teacher as well as Antoniazzi's sons, Romeo and Gaetano. Bisiach went on to employ an astounding number of the greatest modern-Italian makers, including Gaetano Sgarabotto, Rocco Sesto, Afro and Ferdinando Garimberti, Giuseppe Ornati, Vincenzo Cavani, Carlo Carletti, Pietro Paravicini and Igino Sderci. Other makers include Cipriano Briani, Camillo Mandelli, Camillo Colombo, Albert Moglie,Carlo Ferrario, Iginio Siega, Pietro Borghi, Mirco Tarasconi and Ferriccio Vargnolo. Most importantly, Leandro employed his sons, Andrea, Carlo, Leandro II and Giacomo. It is generally regarded that Bisiach's best output was from around 1895-1910 which coincided with the employment of several of his most talented luthiers and which earned him recognition in the form of numerous prizes in violinmaking exhibitions including at Atlanta in 1895-1896, Turin in 1898, Paris in 1900, Milan in 1906 and Brussels in 1910. This period also saw a variety of other bowed instruments being produced in his shop including viola d'amores and an innovative instrument which was essentially a cello-scaled d'amore. These instruments are beautifully crafted with extraordinary precision and feature the "flamming sword" sound holes and carving of a blindfolded Cupid at the head. Bisiach sought fit to include images of these instruments on some of his promotional literature from this period.

In addition to playing the violin from an early age, it is probable that Bisiach made one or more attempts at violinmaking, potentially as a self-taught endeavor, before moving to Milan and training with Riccardo Antoniazzi (b.1853, d.1912) from 1886. In just three short years, Bisiach had opened his own establishment, collaborating with and eventually employing his former teacher as well as Antoniazzi's sons, Romeo and Gaetano. Bisiach went on to employ an astounding number of the greatest modern-Italian makers, including Gaetano Sgarabotto, Rocco Sesto, Afro and Ferdinando Garimberti, Giuseppe Ornati, Vincenzo Cavani, Carlo Carletti, Pietro Paravicini and Igino Sderci. Other makers include Cipriano Briani, Camillo Mandelli, Camillo Colombo, Albert Moglie,Carlo Ferrario, Iginio Siega, Pietro Borghi, Mirco Tarasconi and Ferriccio Vargnolo. Most importantly, Leandro employed his sons, Andrea, Carlo, Leandro II and Giacomo. It is generally regarded that Bisiach's best output was from around 1895-1910 which coincided with the employment of several of his most talented luthiers and which earned him recognition in the form of numerous prizes in violinmaking exhibitions including at Atlanta in 1895-1896, Turin in 1898, Paris in 1900, Milan in 1906 and Brussels in 1910. This period also saw a variety of other bowed instruments being produced in his shop including viola d'amores and an innovative instrument which was essentially a cello-scaled d'amore. These instruments are beautifully crafted with extraordinary precision and feature the "flamming sword" sound holes and carving of a blindfolded Cupid at the head. Bisiach sought fit to include images of these instruments on some of his promotional literature from this period.

A Violin by Riccardo Antoniazzi, Milan 1908

(This instrument is sold)

This Instrument was made during his employment with Monzino & Sons and features the maker's personal brand on the back. His initials R. A. under a cross are encircled.

(This instrument is sold)

This Instrument was made during his employment with Monzino & Sons and features the maker's personal brand on the back. His initials R. A. under a cross are encircled.

Somewhat curious is the fact that while the Riccardo Antoniazzi (like the Cerutis before him) utilized locating pins in the backs of his instruments, neither the instruments of Gaetano Antoniazzi nor the Bisiachs feature this in their work.

The commercial importance of Bisiach's close association with the Antoniazzis cannot be overstated. In addition to the indelible contribution the Antoniazzis made with regard to the success of his workshop's early instruments and the influence they had on his work, through the elder Antoniazzi, he could technically trace his violinmaking-lineage to the great Cremonese masters. This link was something that Bisiach readily advertised and capitalized on. The Antonniazzis were among history's great violin makers however a dwindling market in Cremona compelled them to relocate to Milan by the early 1870's and many of their instruments where unlabeled or made for other firms. Gaetano Antonniazzi likely supplemented his income by working as a furniture maker during stretches throughout the 1850's to 1870's and it was Leandro Bisiach's business savvy which stimulated demand for their work as they helped found the Bisiach firm in 1890. Prior to this, violinmaking in Italy was very much a regional, local or even family affair. Bisiach recognized the growing demand for fine string instruments internationally, especially in the rapidly expanding market in United States, and was the first Italian violin shop to establish international connections in its era. One of Bisiach's innovations was to organize the workshop in such a way as to optimize production in terms of quality and quantity. These goals would have been important in the workshop of Stradivari whose clients and patrons included nobility scattered throughout Europe. To keep up with demand, Stradivari employed from outside his immediate family and divvied up the labor. This working method was very much imported from the methods of the Italian Renaissance artisans. Though much of the knowledge of the craft had still been preserved, Bisiach correctly held the notion that something had been lost between these epochs of violinmaking. Ironically, subsequent makers outside of Italy, such as Nicolas Lupot and J.B. Vuillaume of France as well as many German shops, continued the practice of working in collaboration with assistants at the commercial level while this practice had largely faded in Italy. Bisiach's reintroduction of this organized and collabrative scale of production was transformative.

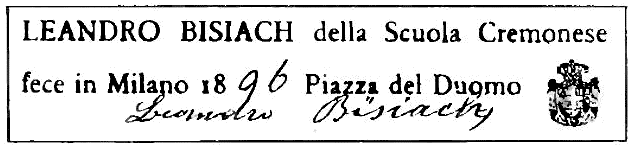

Though perhaps somewhat tenuously linked, via Gaetano Antoniazzi, Bisiach is indeed tied to the old Cremonese school by following the thread though another three generations of the Ceruti family before arriving at Lorenzo Storioni, generally considered to be the last of the classical Cremonese masters. Storioni is believed to have studied with the Bergonzi family. Carlo Bergonzi himself, having purchased casa-Stradivari, perhaps having worked for Stradivari himself and having likely trained with Vincenzo Ruggeri. (It may be worth noting that there is an argument growing in strength that the elder Ceruti, Giovani Battista, studied not with Storioni but directly with Nicola and Carlo II Bergonzi). Perhaps more important than his established historical connection to the old Cremonese masters, Bisiach was linked to them in a philosophical sense. The spirit of the old masters was very much alive in Bisiach's firm. Though some of Bisiach's claims regarding his links to the Cremonese masters may appear to us now as being somewhat exaggerated, perhaps even self-serving or self-mythologizing, recalling one statement where Bisiach claimed to have come into possession of Stradivari's varnish recipe from 1704, it is worth noting that these promotional claims are corroborated (to varying degrees) by evidence. Given his prominence and connections, he would have been better positioned than any other maker (with the possible exception of Giuseppe Fiorini who purchased and preserved most of the authentic Stradivari relics) to acquire resources from the great Cremonese makers. He had amassed an enormous collection of fine instruments and many of the best had passed through his hands at one time or another. Though his shop offered modern instruments at various price points, he is said to have had promoted some of his finest personally made instruments as having been made with remaining wood stock from the old Italian masters. Recent dendrochronology analysis conducted by Peter Ratcliff bears some of this out. Apart from many Bisiach samples analyzed by Mr. Ratcliff (which were from relatively contemporaneous German-sourced wood of high-quality), he informs us that some of Bisiach's instruments do indeed incorporate spruce dating from around 1650 to 1740. Regarding Stradivari's varnish recipe, accounts vary somewhat but Bisiach is said to have either come into possession of documents once belonging to Antonio Stradivari by way of Fanny Rossi (b.1835), widow of Antonio Stradivari's great-great-grandson, Giacomo Stradivari II (b.1822, d.1901) or had access to these documents and upon finding one of Stradivari's varnish formulas among the papers, he either took it, copied it down or photographed it. As of yet, there is no scientific data known to this author which supports or refutes this claim. It is doubtful however, that this claim was made in bad faith. Bisiach was a genuine enthusiast and whether or not the claim is true, Bisiach may well have believed it himself, perhaps out of deep desire for it to be true. Perhaps testing will someday corroborate or refute this claim. Despite being nearly 150 years removed from the golden age of Cremonese violin making and having neither lived nor trained there, it is not merely out of vanity that many of Bisiach's labels read "LEANDRO BISIACH della Scuola Cremonese" (LEANDRO BISIACH of the Cremonese School). Like many of the old Italian masters, his label locates his shop near an important landmark. In Bisiach's case, his shops were located near the famed, Piazza del Duomo. He had relocated his shop several times in the immediate area with its best and most famous location from 1905 at the southwest corner of the Piazza. This is the very heart of Milan and the main roads radiate in all directions from it. The earliest of the great collectors and dealers of fine Italian string instruments, Count Ignazio Cozio di Salabue (b.1755, d.1840) and Luigi Tarisio (b. c.1790, d.1854) were very active here in the century prior. The Duomo (Milan Cathedral), being the religious center, and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II (having been completed in 1877) being the commercial center of Milan, Bisiach's shop could not have been better placed.

Though perhaps somewhat tenuously linked, via Gaetano Antoniazzi, Bisiach is indeed tied to the old Cremonese school by following the thread though another three generations of the Ceruti family before arriving at Lorenzo Storioni, generally considered to be the last of the classical Cremonese masters. Storioni is believed to have studied with the Bergonzi family. Carlo Bergonzi himself, having purchased casa-Stradivari, perhaps having worked for Stradivari himself and having likely trained with Vincenzo Ruggeri. (It may be worth noting that there is an argument growing in strength that the elder Ceruti, Giovani Battista, studied not with Storioni but directly with Nicola and Carlo II Bergonzi). Perhaps more important than his established historical connection to the old Cremonese masters, Bisiach was linked to them in a philosophical sense. The spirit of the old masters was very much alive in Bisiach's firm. Though some of Bisiach's claims regarding his links to the Cremonese masters may appear to us now as being somewhat exaggerated, perhaps even self-serving or self-mythologizing, recalling one statement where Bisiach claimed to have come into possession of Stradivari's varnish recipe from 1704, it is worth noting that these promotional claims are corroborated (to varying degrees) by evidence. Given his prominence and connections, he would have been better positioned than any other maker (with the possible exception of Giuseppe Fiorini who purchased and preserved most of the authentic Stradivari relics) to acquire resources from the great Cremonese makers. He had amassed an enormous collection of fine instruments and many of the best had passed through his hands at one time or another. Though his shop offered modern instruments at various price points, he is said to have had promoted some of his finest personally made instruments as having been made with remaining wood stock from the old Italian masters. Recent dendrochronology analysis conducted by Peter Ratcliff bears some of this out. Apart from many Bisiach samples analyzed by Mr. Ratcliff (which were from relatively contemporaneous German-sourced wood of high-quality), he informs us that some of Bisiach's instruments do indeed incorporate spruce dating from around 1650 to 1740. Regarding Stradivari's varnish recipe, accounts vary somewhat but Bisiach is said to have either come into possession of documents once belonging to Antonio Stradivari by way of Fanny Rossi (b.1835), widow of Antonio Stradivari's great-great-grandson, Giacomo Stradivari II (b.1822, d.1901) or had access to these documents and upon finding one of Stradivari's varnish formulas among the papers, he either took it, copied it down or photographed it. As of yet, there is no scientific data known to this author which supports or refutes this claim. It is doubtful however, that this claim was made in bad faith. Bisiach was a genuine enthusiast and whether or not the claim is true, Bisiach may well have believed it himself, perhaps out of deep desire for it to be true. Perhaps testing will someday corroborate or refute this claim. Despite being nearly 150 years removed from the golden age of Cremonese violin making and having neither lived nor trained there, it is not merely out of vanity that many of Bisiach's labels read "LEANDRO BISIACH della Scuola Cremonese" (LEANDRO BISIACH of the Cremonese School). Like many of the old Italian masters, his label locates his shop near an important landmark. In Bisiach's case, his shops were located near the famed, Piazza del Duomo. He had relocated his shop several times in the immediate area with its best and most famous location from 1905 at the southwest corner of the Piazza. This is the very heart of Milan and the main roads radiate in all directions from it. The earliest of the great collectors and dealers of fine Italian string instruments, Count Ignazio Cozio di Salabue (b.1755, d.1840) and Luigi Tarisio (b. c.1790, d.1854) were very active here in the century prior. The Duomo (Milan Cathedral), being the religious center, and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II (having been completed in 1877) being the commercial center of Milan, Bisiach's shop could not have been better placed.

An example of Bisiach's early labels connect him to the Cremona school and locates his shop at the Piazza del Duomo. It also features the Italian coat of arms.

The Bisiach shop is described as having " large and lofty rooms - choice examples of antique instruments in one room, specimens of his own work in another, and a restoration room occupied by three sons..., Became the most esteemed Italian maker of his time.” according to the Universal Dictionary of Violin & Bow Makers by William Henley. Although Bisiach was an extraordinary violin maker in his own right, it is generally accepted that like Vuillaume, Bisiach increasingly dedicated his time and attention towards other aspects of running his business. Although early examples show Bisiach's masterful work with clear influences of Riccardo Antoniazzi, by 1900 instruments made entirely from start to finish by Bisiach's own hands become exceedingly rare. As stated earlier, in his effort to reproduce the qualities of the Cremonese masterworks, Bisiach divided the labor, organizing his workshop in such a way as to maximize both quality and production as had been done in the shops of Amati and Stradivari. Additionally, like his Cremonese predecessors, his shop crucially employed the use of the internal mold. Instruments produced by his luthiers bearing Bisiach's label are to a degree, an amalgamation of the unique styles and specialties of their makers which were often (although not always) finished off personally by Bisiach in order to meet his approval and carry his name. Much the way a sculptor may have assistants to cut away large chunks of marble so that he may concern himself with the more artistic aspects of the work, Bisiach would typically have had his workers involved in the construction and major graduations of the instruments but generally executed the final thicknessing and varnishing himself (playing and adjusting each one as necessary). Naturally, over time he would have trusted his workers to take on more responsibility and to maintain his high standards. Fortunately, in getting his luthiers to conform to his methods, he did not overly-homogenize the product but rather afforded a great deal of latitude for his workers' personality and sensibility to come out in each instrument. While meticulous execution of the details are of great importance to making a successful violin, a certain amount of spontaneity and inspiration are also needed. Most makers will agree that the unique characteristics of each piece of wood must inform the maker therefore no two violins should be made exactly in the same manner. Here, the Vuillaume shop becomes another useful point of comparison as the stylistic variety found in the examples from the Bisiach shop dwarfs the variety found in that of Vuillaumes' and indeed, the entire golden period of French violinmaking which dominated most of the 19th century. We can find more variety in the examples depicted in this article than we can between Lupot, Pique, Vuillaume and his workers, along with the successive generations of the Chanot, Gand and Bernardel families. This is expanded on in the book, "Emerging National Styles and Cremonese Copies: 19th Century Violinmaking in the Broad Perspective" by Dr. John Huber. Like Vuillaume, Bisiach also became one of the greatest violin connoisseurs of his generation. He amassed grand collections and made careful tracings and measurements of the great instruments which came into his shop. He also established a chronology of the makers and the progression of their respective styles and form. The possibility of studying these instruments would have been a strong draw to many established makers looking to further their own craft and expertise. Bisiach hired the best of them. To contrast with the lives of Bisiach and Vuillame, it's useful to consider that while Vuillaume had daughters, Bisiach had four sons to carry on his legacy. Until recently, the field of violinmaking was occupied almost exclusively by men and sadly, the few women involved were largely unrecognized for their talents.

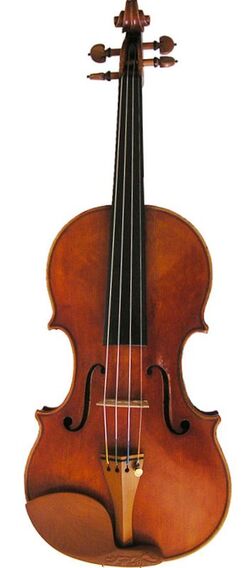

This particular example is a rare copy of a 1696 Stradivarius with a vibrant dark red varnish and striking one-piece back. It has an exceptionally pure and sweet tone, especially in the upper register. The sound is subtle under the ear yet carries extraordinarily well in the concert hall making it an invaluable tool to the musician who simultaneously needs to hear and be heard. Its tonal color and dimension are very malleable and the instrument boasts what so many violinists refer to as the classic “Italian sound”. Despite being a copy of a 1696 Stradivarius, a period when Strads would often exceed far 360mm across the length of the back, this instrument is a very manageable 359mm with very rounded shoulders which allow for more comfortable shifting in the high positions. Bisiach had innumerable Strads for on his work bench providing him with almost limitless access to study and replicate the world's finest string instruments. His family was entrusted by numerous musicians and institutions to maintain and restore the great collections and masterpieces of violinmaking. Like many instruments from this illustrious shop, the varnish is shaded to suggest light antiquing but not in such a way as to reproduce the exact wear patterns of the specific Stadivarius after which it is modeled. It is noteworthy that at the time this instrument was made, Gaetano Sgarabotto was working for Bisiach in his Atilier in Milan. 1904 also marked the year in which Bisiach's teacher and collaborator, Ricardo Antoniazzi, left the Bisiach firm to work for Monzino & Sons.

A Fine Italian Violin by Leandro Bisiach, Milan 1904 'copy of 1696 Stradivarius'

(This instrument is sold)

(This instrument is sold)

A Mint-Condition Violin by Iginio Sderci, Florence, 1956

(This instrument is sold)

(This instrument is sold)

At the time of writing, we are fortunate to have a fine Italian violin by Leandro Bisiach's pupil, Nicolo Igino Sderci (b.1884, d.1983) concurrently with the 1904 Leandro Bisiach violin. We have also had several violins from other Bisiach makers in the shop in recent months. This coincidence has afforded us the opportunity to compare and contrast the mature work of these makers side-by-side.

This Sderci violin from 1956 was made long after Bisiach's death in 1945 and is represented as Sderci's personal work. Despite the major cosmetic and stylistic differences, the manner of construction and choice of materials reveal that certain technical details are consistent between these two instruments. One such detail is the idiosyncratic purfling. This purfling is not only typical of the house-made Bisiach instruments but is also a common thread tying together the personal work of several Bisiach-makers. The Bisiach shop would have likely prefabricated large quantities of purfling for common use of the luthiers as a means of speeding up production. It would have been time-consuming and costly for each maker to have individually produced just enough purfling for each instrument at the appropriate stage of construction. The instruments made by Sderci for the Bisiach shop in Milan would have been made in Sienna and later, in Florence. Bisiach sent materials and instructions to Sderci who he trusted to carry out the work faithfully. The purfling of Bisiach's instruments consistently feature prominently wide "whites" (the middle layer) and delicately thin "blacks" (the outer layer). Curiously, many of the Bisiach-luthiers continued the use of such purfling long after their employment with the master. I've recently had the pleasure of examining a superb violin by Gaetano Sgarabotto and an extraordinary instrument by the tragically doomed, Ferruccio Varagnolo, both of which were made shortly after their employment with Bisach and shared this feature. Another later period Sgarabotto which I've recently examined was an imitation of S. Scarampella and had another sort of purfling altogether. I would like to imagine this was a case of pilfering purfling but the fact that Sderci continued this practice so late into his extraordinarily long career, suggests that this was one of the subtler aspects of Leandro Bisiach's influence and legacy in revitalizing the old Cremonese tradition. The style of the purfling is very reminiscent of Stradivari however, here too, subtle details such as the "bee-stings" diverge from the originals. Additionally, Stradivari's purfling would typically either bisect the locating pins on the back plate or the pin would be slightly behind the inner layer, whereas most Bisiach makers did not use the pins in the construction of their instruments as we see in these examples, yet the 1908 Riccardo Antoniazzi shows the pins just behind the inner purfling layer. The Antoniazzi reliably (but not always) used these pins in their own work. In the case of Riccardo Antoniazzi, his pins were generally below the inner purfling layer and usually offset slightly to the left for the upper pin and right for the lower pin, particularly in the case of instruments composed of a two-piece back. By offsetting the pin from the centerjoint, the maker avoided unnecessary stress that the drill or pin might have otherwise inflicted to the area, perhaps saving the instrument from separating on this otherwise permanent joint.

This Sderci violin from 1956 was made long after Bisiach's death in 1945 and is represented as Sderci's personal work. Despite the major cosmetic and stylistic differences, the manner of construction and choice of materials reveal that certain technical details are consistent between these two instruments. One such detail is the idiosyncratic purfling. This purfling is not only typical of the house-made Bisiach instruments but is also a common thread tying together the personal work of several Bisiach-makers. The Bisiach shop would have likely prefabricated large quantities of purfling for common use of the luthiers as a means of speeding up production. It would have been time-consuming and costly for each maker to have individually produced just enough purfling for each instrument at the appropriate stage of construction. The instruments made by Sderci for the Bisiach shop in Milan would have been made in Sienna and later, in Florence. Bisiach sent materials and instructions to Sderci who he trusted to carry out the work faithfully. The purfling of Bisiach's instruments consistently feature prominently wide "whites" (the middle layer) and delicately thin "blacks" (the outer layer). Curiously, many of the Bisiach-luthiers continued the use of such purfling long after their employment with the master. I've recently had the pleasure of examining a superb violin by Gaetano Sgarabotto and an extraordinary instrument by the tragically doomed, Ferruccio Varagnolo, both of which were made shortly after their employment with Bisach and shared this feature. Another later period Sgarabotto which I've recently examined was an imitation of S. Scarampella and had another sort of purfling altogether. I would like to imagine this was a case of pilfering purfling but the fact that Sderci continued this practice so late into his extraordinarily long career, suggests that this was one of the subtler aspects of Leandro Bisiach's influence and legacy in revitalizing the old Cremonese tradition. The style of the purfling is very reminiscent of Stradivari however, here too, subtle details such as the "bee-stings" diverge from the originals. Additionally, Stradivari's purfling would typically either bisect the locating pins on the back plate or the pin would be slightly behind the inner layer, whereas most Bisiach makers did not use the pins in the construction of their instruments as we see in these examples, yet the 1908 Riccardo Antoniazzi shows the pins just behind the inner purfling layer. The Antoniazzi reliably (but not always) used these pins in their own work. In the case of Riccardo Antoniazzi, his pins were generally below the inner purfling layer and usually offset slightly to the left for the upper pin and right for the lower pin, particularly in the case of instruments composed of a two-piece back. By offsetting the pin from the centerjoint, the maker avoided unnecessary stress that the drill or pin might have otherwise inflicted to the area, perhaps saving the instrument from separating on this otherwise permanent joint.

Sderci's handwriting in pencil as seen through the treble f-hole.

"Fatto a Firenze da Igino Sderci" (made in Florence by Igino Sderci)

The First World War affected Milan and the Bisiachs in numerous ways. Giacomo fought for almost the entire duration of the war. Carlo and Andrea were both called for service however, it seems much of their time was spent performing for troops. Although accounts vary as to whether Leandro Bisiach had closed his shop in Milan or left it running in the capable hands of Andrea, by 1917, the rest of Bisiach family had left the difficulties there, seeking safety and opportunity in Siena. This period would mean many changes for the Bisiach family and shop.

The great arts and music patron, Count Guido Chigi-Saracini (b.1880, d.1965) invited Bisiach to set up shop there so that he could organize and restore the count's immense collection. This opportunity gave Bisiach, by then one of the world's leading experts on fine string instruments, virtually unlimited access to many of the great instruments of violinmaking's golden age. It also helped him further his connections with musicians, composers and other arts patrons.

Giacomo eventually rejoined his family by 1918. Leandro Bisiach Sr. was introduced (presumably by the Count) to Nicolo Igino Sderci (b.1884, d.1983), a talented wood carver of ornate furniture who been declared unfit for service owing to vascular problems in his legs. Sderci, having made a violin without previous instruction, was recognized as an asset and Leandro Bisiach began training him in the art of violinmaking, putting him under Carlo's supervision.

In 1922, the Bisiach family would return to Milan however Carlo married pianist, Daria Guidiand and the couple stayed on in Sienna. Together with Sderci, Carlo continued making instruments there for the shop in Milan. Leandro Bisiach Sr. would send materials and instructions to them and they would send back finished instruments. After the First World War many Bisiach violins were largely the product of the immensely productive and efficient Sderci, as evidenced by their incredibly clean and crisp edge work and slight heaviness. Sderci's varnishing tends to be on the orange (and sometime orange-yellow or orange red) side and is rarely shaded to suggest a slight "antiqueing" as so many of the earlier Bisiach instruments were.

The great arts and music patron, Count Guido Chigi-Saracini (b.1880, d.1965) invited Bisiach to set up shop there so that he could organize and restore the count's immense collection. This opportunity gave Bisiach, by then one of the world's leading experts on fine string instruments, virtually unlimited access to many of the great instruments of violinmaking's golden age. It also helped him further his connections with musicians, composers and other arts patrons.

Giacomo eventually rejoined his family by 1918. Leandro Bisiach Sr. was introduced (presumably by the Count) to Nicolo Igino Sderci (b.1884, d.1983), a talented wood carver of ornate furniture who been declared unfit for service owing to vascular problems in his legs. Sderci, having made a violin without previous instruction, was recognized as an asset and Leandro Bisiach began training him in the art of violinmaking, putting him under Carlo's supervision.

In 1922, the Bisiach family would return to Milan however Carlo married pianist, Daria Guidiand and the couple stayed on in Sienna. Together with Sderci, Carlo continued making instruments there for the shop in Milan. Leandro Bisiach Sr. would send materials and instructions to them and they would send back finished instruments. After the First World War many Bisiach violins were largely the product of the immensely productive and efficient Sderci, as evidenced by their incredibly clean and crisp edge work and slight heaviness. Sderci's varnishing tends to be on the orange (and sometime orange-yellow or orange red) side and is rarely shaded to suggest a slight "antiqueing" as so many of the earlier Bisiach instruments were.

A Violin by Carlo Bisiach, 1926

(This instrument is sold)

(This instrument is sold)

|

Sketch of Carlo Bisiach in his Workshop

|

Sketch of Giacomo Bisiach in his Workshop

|

The aftermath of the August 1943 Bombing of Milan - Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

Of the Bisiach workers, Igino Sderci enjoyed the closest and longest personal and professional relationship with the family. In the Summer of 1926. Sderci and the younger Bisiachs relocated to Florence where they continued working long after Leandro Bisiach's death in 1945. Between the wars, Leandro Bisiach Sr. spent an increasing amount of time in his lavish Villa in Vengono Superiore, just north of Milan. This Villa, now known as "Villa Puccini" is maintained to this day by Giacomo Bisiach Jr. It houses many letters from great musicians and composers to Leandro Bisiach Sr as well as paintings of the maker and many casts and instruments, both finished and unfinished. Although Leandro Bisiach Sr had eventually retired, he continued to oversee aspects of his business and personally make instruments (although in few numbers) until his final years. Though the overall quality of Bisiach instruments tends to be less spontaneous after around 1914, occasional masterpieces (sometimes entirely by Bisiach Sr's hands) do come up from this later period. Presumably due to the semi-itinerate nature of the work during and after WWI, some of Bisiach's instruments from this later period are backdated. These instruments were probably left unfinished for years or even decades before having the final graduations, bass-bar, sound post, varnishing, etc. attended to. Letters by Leandro Bisach Sr. accompanying some of these later instruments to this day, attest to this (although the reason for the delay in finishing the instruments is left unspecified). WWII brought devastation to Milan. In addition to the conscription of working-age men, restricted travel and trade, rationing of basic necessities and shortages of goods, heavy allied bombings were conducted with both strategic and demoralizing objectives. In addition to its military and manufacturing targets, Allied bombers tragically hit civilian populations with the worst of the bombings from August 12-13, 1943. Although there are no known casualties to the Bisiach family, much of the collection was gone by end of the war. Sderci continued to make instruments in his own name as well as for the Bisiach family and occasionally, made instruments in the white for Simone Sacconi. Sderci typically signed his personal instruments inside the back in pencil while sometimes signed instruments which were to carry another maker's label on the inside of the top. Though vascular issues plagued Sderci his entire life, he would become one of the most prolific violinmakers in history, finishing some 700 instruments before his death in 1983 at the age of 99. Sadly, his son would son soon follow, passing away in 1986. Many of Sderci's materials (including some which had come from the Bisiachs) had fallen into neglect but were salvaged thanks to the efforts of the maker Paolo Vettori who, to this day, maintains them for posterity. His family, violinmakers themselves, have infused aspects of the Milanese tradition which Leandro Bisiach had established and reconstructed from the last remnants of the great Cremonese traditions. His impact was also spread by Sgaraboto who had directed the violinmaking school in Parma, which although it was short lived, was profoundly influential. Renato Scrollavezza (b.1927, d.2019), who was arguably the most influential violinmaker of the latter half of the 20th century, revitalized the Parma violinmaking school. Although initially self-taught, he went on to receive instruction from Sgarabotto, Leandro Bisiach II, Carlo Bissiach, Sderci, Sacconni and many other makers (most with a direct connection to the Bisiach shop). Scrollavezza also had the distinction of being the curator of Paganini's 'Il Cannone". Many of today's makers have studied with him and they, as well as his daughter, Elisa, carry on the tradition today.

Article by: C.M.M.

Article by: C.M.M.

Leandro Bisiach I (bottom left) with his sons & Igino Sderci (bottom right).

Trivia

Legendary violin virtuoso, Nathan Milstein, is known to have owned at least one Bisiach.

Richard Tognetti, leader of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, helped Academy Award winning actor, Russell Crowe select a Bisiach violin for use in the 2003 film, Master & Commander.

Numerous string players have owned violins by Sderci including the First Associate Concert Master of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Nathan Cole, according to his Instagram and posts on theviolinist.com.

Richard Tognetti, leader of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, helped Academy Award winning actor, Russell Crowe select a Bisiach violin for use in the 2003 film, Master & Commander.

Numerous string players have owned violins by Sderci including the First Associate Concert Master of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Nathan Cole, according to his Instagram and posts on theviolinist.com.

Bibliography

Eric Blot, Un secolo di Liuteria Italiana 1860–1960 – A century of Italian Violin Making – Emilia e Romagna I, Cremona 1994. ISBN 88-7929-026-6

Blot, Eric (1994). "Lombardia e Veneto II". Un secolo di liuteria italiana, 1860-1960 - A century of Italian violin making. Cremona: Turris. ISBN 88-7929-008-8.

Hamma, Walter. Italian Violin Makers (8th ed). p. 646-647. Messiah Enterprise Corporation Wilhelmshaven 1993

La Liuteria Italiana / Italian Violin Making in the 1800s and 1900s – Umberto Azzolina

I Maestri Del Novicento – Carlo Vettori

La Liuteria Lombarda del '900 – Roberto Codazzi, Cinzia Manfredini 2002

Emerging National Styles and Cremonese Copies: 19th Century Violinmaking in the Broad Perspective by Dr. John Huber, Messiah Enterprise Corporation 2005

Dictionary of 20th Century Italian Violin Makers – Marlin Brinser 1978

Dictionnaire Universel del Luthiers – René Vannes 2003

Natale Gallini, Franco Gallini, Museo degli strumenti musicali, Milano, 1963.

BISIACH, Giuseppe, detto Leandro, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. URL consultato l'11 marzo 2013

Gli ultimi dei Bisiach di Paolo Fornaciari in Arte Liutaria n.10/88

"The Bisiach Family Heritage" by Phillip J. Kass for World of Strings, PUBLISHED AUTUMN 1983 BY WILLIAM MOENNIG & SON, LTD., 2039 LOCUST STREET, PHILA., PA. 19103

Violin Makers (Documentary) Paolo Parmiggiani and Andrea Zanrè, Edizioni Scrollavezza & Zanrè (2013)

Luigi Tarisio, part 1The life of the itinerant Piedmontese violinist whose ‘whole soul was in fiddles’By John Dilworth, with the assistance of Carlo Chiesa

The Strad - November 2020 p. 38-44. Filimonov, Gennady Carlo Bisiach/ Siena Years/ Igino Sderci(DISPATCHES FROM THE FRONT LINE)

Multiple, Authors (2004). Cacciatori, Fausto (ed.). Liuteria in Toscana I liutai del Novecento – Violin-Making in Tuscany Violin-Makers of the 20th Century. Cremonabooks. pp. 76–85. ISBN 88-8359-055-4.

The Strad - June 1973: p. 70-79. Mell, Albert Carlo Bisiach (1892–1968)

The Strad - July 1973: p. 135-145. Mell, Albert Carlo Bisiach (1892–1968)

The Art of Violin Making in Italy : Arnaldo Bonaventura (from Arte Liutaria by Carlo Vettori)

A WORTHY INHERITOR OF HIS FATHER'S ART: CARLO BISIACH : Pardo Fornaciari (from Arte Liutaria by Carlo Vettori)

I Maestri Del Novicento - Carlo Vettori

Dictionary of 20th Century Italian Violin Makers - Marlin Brinser 1978

Vannes, Rene (1985) [1951]. Dictionnaire Universel del Luthiers (vol.3). Bruxelles: Les Amis de la musique. OCLC 53749830.

William, Henley (1969). Universal Dictionary of Violin & Bow Makers. Brighton; England: Amati. ISBN 0-901424-00-5.

The Legend of Italian Violins: Brescian and Cremonese Violin Makers 1550–1950, Chi Mei Culture Foundation, Wen-Lo Shi, Taiwan, 2009.

Liuteria Italiana in Cafaggiolo, Florence, in 1989

Great Italian Violinmaking, Artemio Versari, Edizioni Novecento, Cremona, 2009

Meister Italienischer Geigenbaukunst - Walter Hamma 1964

Italian & French Violin Makers - Jost Thoene 2006

Blot, Eric (1994). "Lombardia e Veneto II". Un secolo di liuteria italiana, 1860-1960 - A century of Italian violin making. Cremona: Turris. ISBN 88-7929-008-8.

Hamma, Walter. Italian Violin Makers (8th ed). p. 646-647. Messiah Enterprise Corporation Wilhelmshaven 1993

La Liuteria Italiana / Italian Violin Making in the 1800s and 1900s – Umberto Azzolina

I Maestri Del Novicento – Carlo Vettori

La Liuteria Lombarda del '900 – Roberto Codazzi, Cinzia Manfredini 2002

Emerging National Styles and Cremonese Copies: 19th Century Violinmaking in the Broad Perspective by Dr. John Huber, Messiah Enterprise Corporation 2005

Dictionary of 20th Century Italian Violin Makers – Marlin Brinser 1978

Dictionnaire Universel del Luthiers – René Vannes 2003

Natale Gallini, Franco Gallini, Museo degli strumenti musicali, Milano, 1963.

BISIACH, Giuseppe, detto Leandro, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. URL consultato l'11 marzo 2013

Gli ultimi dei Bisiach di Paolo Fornaciari in Arte Liutaria n.10/88

"The Bisiach Family Heritage" by Phillip J. Kass for World of Strings, PUBLISHED AUTUMN 1983 BY WILLIAM MOENNIG & SON, LTD., 2039 LOCUST STREET, PHILA., PA. 19103

Violin Makers (Documentary) Paolo Parmiggiani and Andrea Zanrè, Edizioni Scrollavezza & Zanrè (2013)

Luigi Tarisio, part 1The life of the itinerant Piedmontese violinist whose ‘whole soul was in fiddles’By John Dilworth, with the assistance of Carlo Chiesa

The Strad - November 2020 p. 38-44. Filimonov, Gennady Carlo Bisiach/ Siena Years/ Igino Sderci(DISPATCHES FROM THE FRONT LINE)

Multiple, Authors (2004). Cacciatori, Fausto (ed.). Liuteria in Toscana I liutai del Novecento – Violin-Making in Tuscany Violin-Makers of the 20th Century. Cremonabooks. pp. 76–85. ISBN 88-8359-055-4.

The Strad - June 1973: p. 70-79. Mell, Albert Carlo Bisiach (1892–1968)

The Strad - July 1973: p. 135-145. Mell, Albert Carlo Bisiach (1892–1968)

The Art of Violin Making in Italy : Arnaldo Bonaventura (from Arte Liutaria by Carlo Vettori)

A WORTHY INHERITOR OF HIS FATHER'S ART: CARLO BISIACH : Pardo Fornaciari (from Arte Liutaria by Carlo Vettori)

I Maestri Del Novicento - Carlo Vettori

Dictionary of 20th Century Italian Violin Makers - Marlin Brinser 1978

Vannes, Rene (1985) [1951]. Dictionnaire Universel del Luthiers (vol.3). Bruxelles: Les Amis de la musique. OCLC 53749830.

William, Henley (1969). Universal Dictionary of Violin & Bow Makers. Brighton; England: Amati. ISBN 0-901424-00-5.

The Legend of Italian Violins: Brescian and Cremonese Violin Makers 1550–1950, Chi Mei Culture Foundation, Wen-Lo Shi, Taiwan, 2009.

Liuteria Italiana in Cafaggiolo, Florence, in 1989

Great Italian Violinmaking, Artemio Versari, Edizioni Novecento, Cremona, 2009

Meister Italienischer Geigenbaukunst - Walter Hamma 1964

Italian & French Violin Makers - Jost Thoene 2006